3.5 Case Study: Nudge Learning and Gamification: Duolingo

Personal report from Graham Attwell:

When I discuss the use of artificial intelligence in education with teachers, the question I get asked most often is for examples. I can understand why. Although there are endless reports about artificial intelligence in the media, it can still sound a somewhat abstract concept when it is applied to teaching and learning.

So, I volunteered to say something about Duolingo, as a researcher working in this area but more importantly as a learner. Let’s explain my background. A few years ago, I moved to live in Spain. I didn’t speak any Spanish at the time (apart from Buenos Dias). Rather nervously, I signed up for a course at a local language school. And I hated it. I see myself as not being good at languages or more accurately learning languages. And the course, despite being one-to-one with the teacher, only confirmed my opinion. I went once a week, and each week was heavily focused on grammar. The next week went on to some new grammar, regardless of whether I had learned or understood the previous week’s lesson. I was given some homework – basically photocopies of a Spanish grammar textbook. And after about six or seven lessons I dropped out.

It was time to try something new, so I signed up for online learning. Decided to try Duolingo. Firstly, it was free, so I had nothing to lose. Secondly, I had briefly tried it a few years ago in my not very successful attempt to learn German. And thirdly, I was curious about the hype. Would Duo do it for me?

Duolingo claims to offer free personalized education. With more than 500 million learners, they say, Duolingo has the world’s largest collection of language-learning data at its fingertips. Duolingo currently offers 40 different languages, 37 of which are for English speakers. Although I don’t know this from my personal experience, it seems some of these are better supported than others, and this depends on the popularity of the language.

Everyone learns in different ways. For the first time in history, we can analyze how millions of people learn at once to create the most effective educational system possible and tailor it to each student.

They claim their ultimate goal is to give everyone access to a private tutor experience through technology.

Dua Linga goes on to say that it’s hard to stay motivated when learning online, so they made Duolingo so fun that people would prefer picking up new skills over playing a game.

“We believe that anyone can learn a language with Duolingo. Our free, bite-size lessons feel more like a game than a textbook, and that’s by design: Learning is easier when you’re having fun.

But Duolingo isn’t just a game. It’s based on a methodology proven to foster long-term retention, and a curriculum aligned to an international standard.”

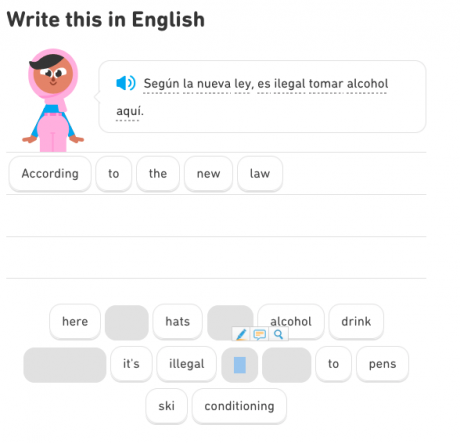

OK how does it work and where does the AI come in. It’s a bit difficult to explain the structure but I’ll give it a go. At the centre of Duolingo is a series of scaffolded lessons.

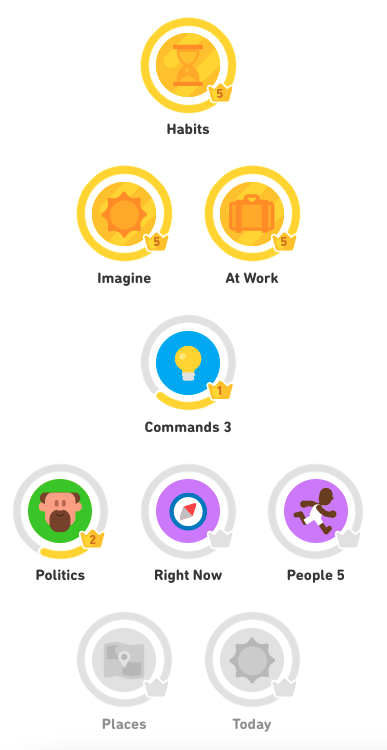

Duolingo courses are organized into a series of units, with about 25-30 what they call skills (more commonly these might be seen as modules, per unit. Each unit has five levels of difficulty and each level has 5 to 6 lessons. Skills are designed around themes for example travel. The vocabulary taught in the skill is around that theme, for instance, hotels, airports, passports. Grammar topics tend to be consistent across lessons within a skill. Lessons typically consist of 12-15 exercises designed to teach some vocabulary and/or grammatical concept.

Duolingo courses are organized into a series of units, with about 25-30 what they call skills (more commonly these might be seen as modules, per unit. Each unit has five levels of difficulty and each level has 5 to 6 lessons. Skills are designed around themes for example travel. The vocabulary taught in the skill is around that theme, for instance, hotels, airports, passports. Grammar topics tend to be consistent across lessons within a skill. Lessons typically consist of 12-15 exercises designed to teach some vocabulary and/or grammatical concept.

Previously taught concepts return in more complex contexts in future skills. The five levels for each skill provide a scaffolded learning experience, where learners review the same vocabulary or grammatical concepts in increasingly difficult contexts. The sequence of lessons are based on the same content but using different exercise types from passive recognition, such as matching a second language word/picture pair with the corresponding word in the first language to more difficult, requiring recall and translation.

Access to each skill opens up as the foundation level in previous skills are completed. This means learners have choices in how they progress. Personally, I prefer to do one skill set at a time, but others may choose to have several on the go at the same time.

At any time, the learner can go back and practice skills they have already completed, with changing content over time.

Now a bit about the AI, in the form of adaptive learning content. If you get the answer to an exercise wrong, not only is it repeated at the end of the lesson until you get it right, but the system tries to provide another example using the vocabulary or grammar which you have got wrong. It’s a bit hit or miss and can get irritating when the problem was a typo, but overall, I like it. Of course, there are many correct ways of saying the same thing in many contexts – and I read somewhere that for each exercise, Duolingo has 50 or sixty different versions held in its database (it seems there is a way of seeing these on the Chrome browser).

As well as the lessons which are at the heart of Duolingo, there is a growing bank of hundreds of short stories (at least in the Spanish/ English version with interactive exercises – questions and sentence completion and vocabulary tests included and podcasts which in Spanish turn up regularly in the top five educational podcasts lists provided by Apple.

Lets think a bit about the pedagogy. Pretty obviously Duolingo has a core belief in scaffolded practice – pretty much drill and learn. But motivation is central to Duolingo and this is where the gamification come in. I’m not going to describe all the bits and pieces of gamification but will say something of what works for me – and remember I was hardly a motivated learner before I started my Duolingo course.

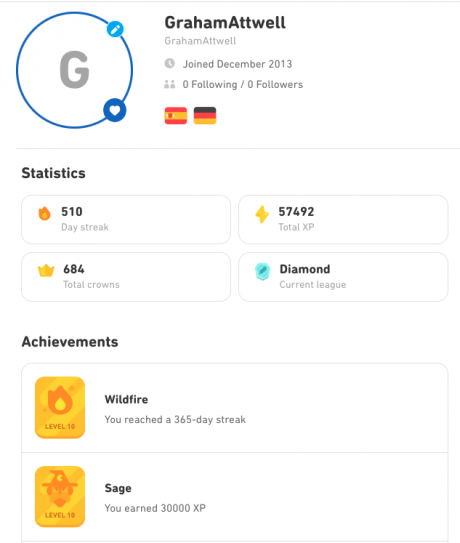

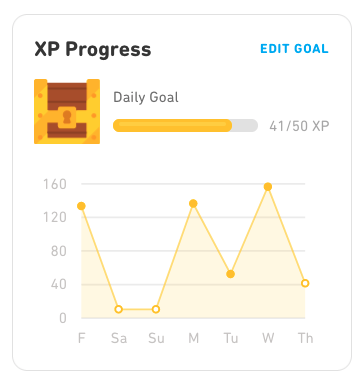

Duolingo is big on motivation and particularly that learners should practice at least a little very day. To this end they have developed streaks which count the number of days that you have continuously been learning (my streak I am proud to say now stands at 509 days). When their research found that those breaking a streak became demotivated, they introduced streak freezes – with learners able to buy a weekend streak on Fridays and an emergency streek freeze using the platform currency – the Lingot (Lingots are accumulated for each lesson competed and for hitting a learner defined target for each days learning). Regular learning is bolstered by almost daily nudges – by email and phone messaging.

Duolingo is big on motivation and particularly that learners should practice at least a little very day. To this end they have developed streaks which count the number of days that you have continuously been learning (my streak I am proud to say now stands at 509 days). When their research found that those breaking a streak became demotivated, they introduced streak freezes – with learners able to buy a weekend streak on Fridays and an emergency streek freeze using the platform currency – the Lingot (Lingots are accumulated for each lesson competed and for hitting a learner defined target for each days learning). Regular learning is bolstered by almost daily nudges – by email and phone messaging.

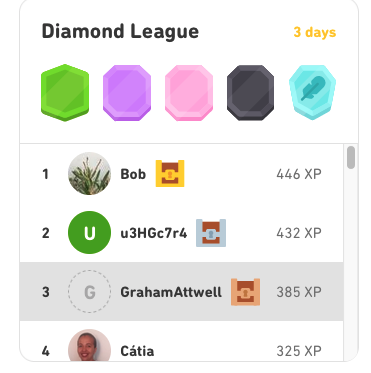

Another central gamification feature is the league tables which are renewed weekly. There are 30 learners in each league, with promotion and relegation for the top and bottom five. There is something like seven levels of leagues, the top being the Diamond League. League positions depend on the number of Lingots accumulated in a week. As well as from lessons, Lingots can also be earned through stories. At first, I didn’t like the competitive nature of the leagues, but over time have found that seeing the achievement of others in the league motivates me to spend more time learning. And a recently added feature allows you to compare your last seven days learning with any other member of your league.

What I have been describing is basically the computer browser version of Duolingo. I suspect more learners use the mobile version. I think this is  where the gamification really comes into its own with all kinds of games liked timed challenges and vocabulary tests. I never really used the mobile version until recently when I found myself ‘playing’ when I had short breaks or was traveling. And for someone who is not really into mobile games I find it a lot of fun!

where the gamification really comes into its own with all kinds of games liked timed challenges and vocabulary tests. I never really used the mobile version until recently when I found myself ‘playing’ when I had short breaks or was traveling. And for someone who is not really into mobile games I find it a lot of fun!

As well as individual learners, Duolingo seems to be making big efforts to get their platform incorporated in school language provision.

Now what are the downsides to Duolingo. I think its very good at teaching vocabulary and grammar. Where it perhaps is not so good is in learning to speak a language. Although there are occasional nudes to read sentences aloud to yourself and in the mobile version there are spoken sentence exercises which either are ‘passed’ or you are asked to read it again, that is about it. Before Covid 19 Duolingo was making an effort to set up user meet ups in local communities, but this seems to have fallen foul of the pandemic. Now they are promoting both free and paid for online sessions with a tutor in small groups.

Finally, something about data. Duolingo obviously has a huge and growing store of user data, including results from tests at the end of each group of units. The results are not shown to users but those on premium accounts can try a test whenever they like – although it seems to me the results are a bit random – aiming to increase motivation rather than provide any real formative feedback. Duolingo publishes some results of their research on one of their websites – which seems mainly around site and application design as well as a recent post around design of assessments. But the treasure trove of data must surely be a rich picking for understanding and advancing language learning, particularly online.

Finally, something about data. Duolingo obviously has a huge and growing store of user data, including results from tests at the end of each group of units. The results are not shown to users but those on premium accounts can try a test whenever they like – although it seems to me the results are a bit random – aiming to increase motivation rather than provide any real formative feedback. Duolingo publishes some results of their research on one of their websites – which seems mainly around site and application design as well as a recent post around design of assessments. But the treasure trove of data must surely be a rich picking for understanding and advancing language learning, particularly online.

Activity

The best way to learn about online learning programs are to try them out. Set up a free account in Duolingo and spend a few minutes trying it. What do you like? What don’t you like?

Reflection

There has been some controversy about nudging. Do you think your students would benefit from regular nudges? Or would they find them intrusive and annoying?

Gamified learning is becoming popular. Do you think games are a good way of learning? Have you ideas for games that you could develop for your subject?